Need help?

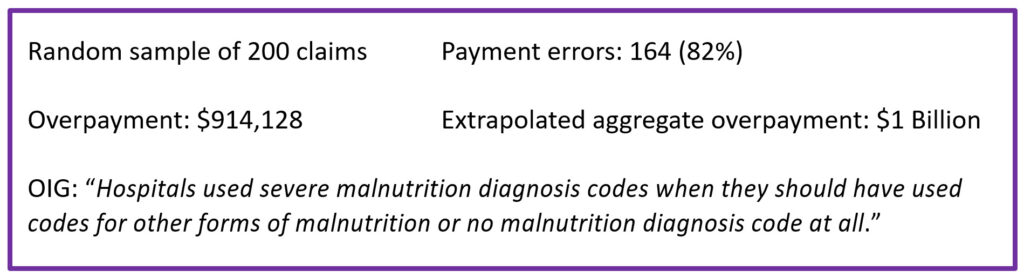

[email protected]The CMS Office of Inspector General (OIG) released a report in July 2020 claiming that hospitals over-billed Medicare approximately $1 billion in a two-year period for claims that included a secondary diagnosis of severe malnutrition.

The OIG audited 200 claims randomly selected from a total of 224,175 claims from fiscal years 2016 and 2017 that contained code E43 (unspecified severe protein-calorie malnutrition) or E41 (nutritional marasmus) which are classified as MCCs.

OIG audit findings. The auditors found that, in 164 of the 200 claims reviewed, the diagnosis of severe malnutrition was not clinically supported. The denials were based on ASPEN diagnostic criteria and lack of evidence that the treatment was congruent with the severity of illness in intensity and complexity. In other words, many of the 164 claims failed to show the complex decision-making and intense intervention expected for severe malnutrition.

Clinical validation of severe malnutrition. For many years, our CDI Pocket Guide® has cautioned hospitals and providers that the clinical validity of any diagnosis depends, in part, on providing the management expected for the condition. For example, a diagnosis of gram-negative or staph pneumonia will not be considered clinically valid if azithromycin is the only antibiotic administered; a diagnosis of acute kidney injury (AKI) will not be considered clinically valid without hydration and monitoring of creatinine levels for improvement.

In the case of severe malnutrition, things become a bit more complicated since many patients may meet two ASPEN criteria for severe malnutrition but not receive the intense management or treatment expected with this diagnosis. Much like marasmus and kwashiorkor in underdeveloped countries, severe protein-calorie malnutrition (code E43) in the United States should be considered a serious, potentially life-threatening situation requiring carefully monitored, aggressive management.

What treatment is congruent with severe malnutrition? While a patient who has non-severe malnutrition may be seen by a nutritionist, who would likely recommend a nutritious diet along with one to two daily liquid supplements (e.g., Boost), a patient with severe malnutrition would be expected to receive some of the following:

Let's look at two cases to illustrate the difference.

Case study #1: A 91-year-old female with a history of dementia was admitted with rectal pain and severe fecal impaction. Colonoscopy revealed stercoral colitis and multiple mucosal ulcers. The gastroenterologist diagnosed “severe protein-calorie malnutrition.” The nutritionist documented “inadequate calorie intake; 8% weight loss in last 1.5 months” and “high risk.” The patient’s BMI was 24 (upper end of normal). The patient was treated with IV Cipro and Flagyl, advancement of diet as tolerated, with Boost twice a day.

Case study #2: An 80-year-old female with congestive heart failure who lives alone at home was admitted after two weeks of increasingly severe diarrhea and abdominal pain. She had been recently treated with antibiotics for recurrent urinary tract infection. Physical exam revealed a frail, thin female who needs assistance getting up from a chair and generalized weakness. Lab results included CRP 5.5 (range 0.3-1.0), albumin 2.8 (range 3.4-5.4); prealbumin 11.0 (range 15-36), and positive C. diff toxin. She was diagnosed with C. diff colitis and transferred to rehab after a five-day hospital stay. The nutritionist documented a 6% weight loss over the past month and a BMI of 19.3. Appetite was poor and the patient consumed < 75% calories for 3 weeks. No obvious muscle mass or subcutaneous fat loss. She was treated with Boost 3-4 times daily and daily calorie counts to monitor calorie intake.

Which of these patients would be considered to demonstrate "severe” malnutrition?

Patient #1 meets the ASPEN criteria for severe malnutrition due to reduced calorie intake and weight loss in an acute setting, but her treatment (Boost twice a day) would likely be interpreted as mild or moderate malnutrition, despite the fact that her dementia likely means she will need ongoing nutritional monitoring. Also, her BMI indicates she is not severely malnourished. Patient #2 meets GLIM (but not ASPEN) criteria for severe malnutrition, because of her BMI of 19.3 (< 22 if ≥ 70 years old), documented reduced nutritional intake for over two weeks, and evidence of acute disease with severe systemic inflammation (C. diff colitis with elevated CRP). The patient’s documented treatment (3-4 daily liquid supplements plus daily calorie counts) is more consistent with a diagnosis of severe malnutrition.

How to prevent malnutrition denials. As usual, the answer is in the documentation—of both the diagnostic criteria met and the treatment that matches the severity of the diagnosis.

Select either the ASPEN or GLIM criteria, not both. Hospitals should establish a diagnostic standard and organization guidelines for malnutrition and involve the compliance department. Choose either ASPEN or the more recent international GLIM criteria and use the criteria consistently across the institution. Be sure your nutritionist documentation includes the specific ASPEN or GLIM criteria that are met. Educate clinicians.

Ensure the treatment plan is as intense as the diagnosis is severe. If the treatment plan does not contain some of the treatment indicators above for "severe malnutrition," the diagnosis of severe malnutrition is likely to be considered invalid.

Appealing severe malnutrition denials. As a result of this audit, CMS has instructed its audit contractors to recover the 164 identified overpayments and to review additional claims from the 224,000+ audit sample to recover additional overpayments for severe malnutrition. So, get ready to defend your claims.

Do not appeal all denials. If after a review of the medical record, the documentation clearly does not meet the clinical criteria or treatment expected for severe malnutrition, do not appeal—it will waste everyone’s time.

If the diagnosis of severe malnutrition is clinically supported, however, include these three elements in your appeal letter:

In the above case studies, case #1 would likely not succeed in an appeal.

Although the OIG audit suggests that severe malnutrition is over-reported, the major nutrition societies report widespread under-recognition and under-treatment of malnutrition. Clearly, there is a need for authoritative diagnostic standards and clinician education, but the best way we can help determine the prevalence of malnutrition is to ensure accurate medical record documentation.

Get our CDI Pocket Guide® for more information on malnutrition.

Receive updates on new Resources, Products, and Events.